COVID-19 amplifies the risks of hot weather.

To reduce heat-related illness and loss of life authorities and communities should prepare for hot weather and heatwaves – in addition to managing COVID-19 – before extreme heat strikes.

This information series aims to highlight issues and options to consider when managing the health risks of extreme heat during the COVID-19 pandemic.

WHO Resources

Technical Brief

Global Heat Health Information Network (GHHIN)

2020

Checklist

Q&A

General Considerations and Evidence

-

Updated: 22 May 2020 All people can potentially fall ill to both heat stress and COVID-19 if exposed. However, COVID-19 has further amplified the physiological and social susceptibility of many vulnerable groups in hot weather. People who are considered the most vulnerable to both COVID-19 and high ambient heat are:

- Older people (>65 years and especially >85years);

- People with underlying health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, kidney disease, diabetes / obesity, mental health issues (psychiatric disorders, depression);

- Essential workers who work outdoors during the hottest times of the day or who work in places that are not temperature controlled;

- Health workers and auxiliaries wearing personal protective equipment;

- Pregnant women;

- People living in nursing homes or long-term care facilities, especially without adequate cooling and ventilation;

- People who are marginalized and isolated (experiencing homelessness, migrants with language barriers, old people living alone) and those with low income or inadequate housing, including informal settlements;

- People on medication: some medication for the diseases listed above impairs thermoregulation. The impact of treatment for COVID-19 is currently unknown but should be monitored to assess any additional vulnerability.

- People who have, or are recovering from, COVID-19 (which can be associated with acute kidney injury).

- People in prison, or residential institutions especially if cooling measures are not in place.

-

There is insufficient evidence to suggest that seasonality will play a role in transmission rates of SARS-CoV-2. At this phase of the pandemic, other factors are likely to be significantly more important, e.g. susceptibility in the population and mitigating behaviours.

-

- Human exposure to ambient ozone and extended heat conditions can exacerbate cardiopulmonary disease and respiratory illnesses. Whether combined exposure to heat and ozone can also aggravate COVID-19 symptoms and prognosis is under evaluation, but has not yet been fully established.

- People with prior long-term exposure to high levels of air pollution might face the combined effect of increased vulnerability to heat stress and increased vulnerability to more severe COVID-19 symptoms.

- Recent observations of air pollution (e.g. nitrogen dioxide (NO2), airborne particulate matter (PM)) show a downward trend in primary pollutants due to decreased transport and economic activities as a result of COVID-19 control measures. How these recent changes in air quality will affect extreme heat, ambient ozone levels and heat-related health impacts has not yet been established.

Issues for Health Workers

-

Yes, provided physical distancing guidelines can be followed. Outdoor public spaces offer important mental and physical health benefits, provided physical distancing guidelines can be followed. Local or national government will determine the extent to which outdoor public spaces can be used for cooling, taking into consideration whether or not it is possible to limit transmission of COVID-19. Lower-income neighbourhoods may have less shade in outdoor public spaces, so consider equity and actions that can be taken in these less well-served areas (Harlan et al., 2007; Mitchell & Chakraborty, 2014).

-

Be careful to not mistake hyperthermia for fever. Differential diagnosis between heat illness and COVID-19 is critical to facilitate accurate testing, diagnosis and treatment, and prevent contraindications of treatment. A heat-stressed individual may also be ill (with mild to severe symptoms of overheating) and can potentially be mistaken as being febrile. It is important that they are monitored until hyperthermia subsides. If symptoms persist, seek medical advice immediately. If someone has been exercising and/or was exposed to heat, let him/her rest in a cool environment for at least 30 minutes. If body core temperature remains elevated during this time, it may be fever - consult a health expert immediately and explain the person's condition. If you observe a substantial drop in body core temperature (of 0.5°C or more, towards the normal 37°C) and the individual feels better after resting in a cool environment, it is more likely to be heat-stress related. In this case, ensure that the individual is hydrated and has no other indications of COVID-19 infection.

-

There are three ways to reduce heat stress while wearing PPE:

- Start cool

- Reduce rises in body core temperature at work

- Improve thermal tolerance through acclimatization and fitness

Issues for heat action planners and city authorities

-

The indoor heat exposure experienced by residents of urban informal settlements can be dangerously high, and staying indoors during a heatwave for inhabitants of informal settlements will not be possible, especially during the hottest times of the day, regardless of physical distancing mandates that may be in place due to COVID-19. Additional measures therefore need to be introduced to reduce the spread of COVID-19, while allowing people to leave their homes to seek respite from the heat. Such provisions can include the frequent disinfection of high-frequency touch-points such as public drinking-water taps, or the distribution of face masks. Access to water is especially crucial during a heatwave.

-

It is important to empower and coordinate with government and non-governmental social services to reach those most vulnerable to the risks of hot weather and COVID-19. Local government, along with offices and services for the aging, child and family services, services for people living with disabilities and other social safety net programmes are all key partners. These offices can be effective ways to reach vulnerable people during hot weather, as most will have established virtual and tele-access options for continuing support during COVID-19. It is also important to coordinate with prisons and other types of residential institutions, especially if they lack air-conditioning. Civil society and religious institutions that perform social service functions are important too. This could include places of worship, community associations and clubs, food banks, homeless shelters and volunteer organizations such as the Red Cross Red Crescent Societies. Ensuring that these agencies and organizations are aware of the heightened risks during hot weather and are equipped to provide basic information on heat awareness, along with referrals to more information and services, will help to reduce community vulnerability. Each of these groups can play a role in safely reaching (virtually or in-person) people who are highly vulnerable to the combined risks of extreme heat and COVID-19, if provided with the right training and coordinated support.

-

Yes, provided physical distancing guidelines can be followed. Outdoor public spaces offer important mental and physical health benefits, provided physical distancing guidelines can be followed. Local or national government will determine the extent to which outdoor public spaces can be used for cooling, taking into consideration whether or not it is possible to limit transmission of COVID-19. Lower-income neighbourhoods may have less shade in outdoor public spaces, so consider equity and actions that can be taken in these less well-served areas (Harlan et al., 2007; Mitchell & Chakraborty, 2014).

-

Decisions need to be made locally about whether to open a cooling centre during the COVID-19 pandemic. This will depend on factors such as the law, the availability of staff and the ability to ensure physical distancing guidelines are followed. Staying at home instead of using the public/local cooling centres may compromise health for vulnerable groups during heatwaves. Allow the public (in particular vulnerable people) to use cooling and hydration facilities to limit negative heat-stress effects without compromising COVID-19 guidelines (physical distancing/cleaning of water bottles/cooling pools or other shared facilities). Ensure that cooling centres are safe and develop and implement communication strategies specific to preventing COVID-19 in cooling centres using information from trusted sources such as local or national health authorities or the WHO. Options for modifying the cooling centre network might include opening only select cooling centre locations in highly vulnerable parts of the community, maximizing the use of outdoor cool spaces, or increasing at-home cooling via energy utility assistance.

-

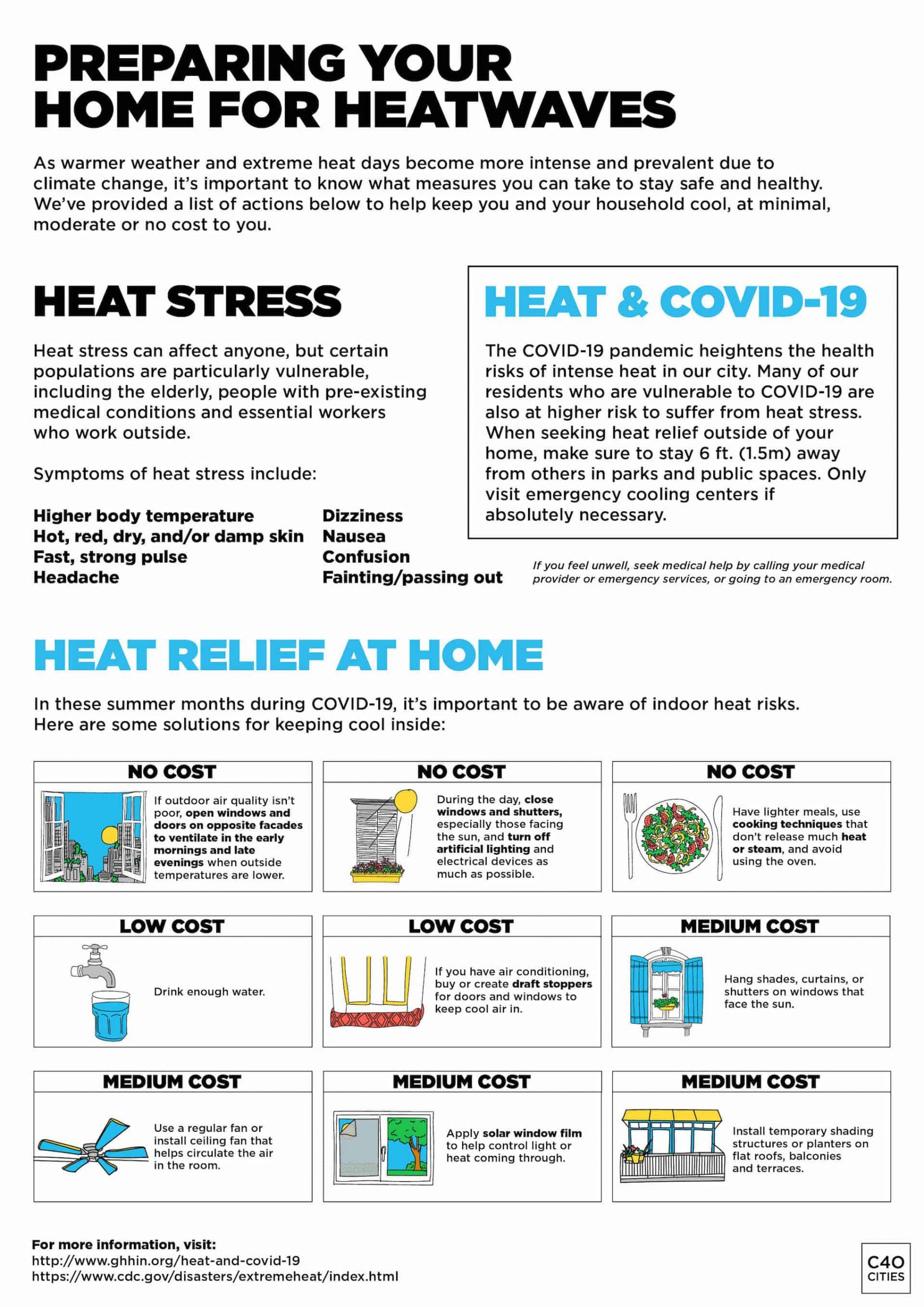

Residents can use low-cost measures to cool their homes and themselves when air conditioning is not available. Strategies include: closing windows and blinds during the day, creating nighttime cross breezes, drinking cool water before feeling thirsty, and wetting clothing.

-

Air conditioning and ventilation systems that are well-maintained and operated should not increase the risk of virus transmission. Fans are safe in single occupancy rooms. Fans for air circulation in collective spaces should be avoided when several people are present in this space. All air conditioning and industrial ventilation systems for both residential and high occupancy buildings (government buildings, schools, hotels, and hospitals) should be inspected, maintained, and cleaned regularly to prevent transmission. Even in well-ventilated environments, people should continue following recommendations of physical distancing and frequent hand hygiene. Set temperatures between 24oC/75 oF and 27oC/ 80.5oF for cooling during the warmer weather, and RH between 50% and 60%. If the use of fans is unavoidable, increase outdoor air exchange, and minimize air blowing from one person directly at another should be taken to reduce the potential spread of any airborne or aerosolized viruses.

-

Updated 22 May 2020 Communication strategies on heatwaves, targeting the general public should be scaled up to raise awareness of heightened vulnerabilities to hot weather due to the COVID-19 pandemic. At-home safety checks of the most vulnerable can be undertaken. Review plans for in-home safety checks of the most vulnerable during hot weather in the context of COVID-19, ensuring the health and safety of outreach staff and volunteers through training and the provision of personal protective equipment (PPE). Where possible, increase telephone contacting and transition at-home safety checks for the most vulnerable into remote approaches (telephone and videocall).

National Guidance on Heat and COVID-19

Canada

France

Germany

India

The Netherlands

United Kingdom

United States of America

Action Examples

-

This information is intended to help multiple audiences better understand the risk conditions of extreme-heat during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cross-cutting topics covered in Q&A set 1 (general considerations and evidence) may be relevant to multiple audiences; Q&A set 2 (issues for health workers) addresses issues relevant to health workers and health facility managers; and Q&A set 3 (issues for heat action planners and city authorities) addresses issues relevant to city governments or institutions supporting heat preparedness and management. Supplementary checklists are also provided.

The questions were provided by public health agencies and city governments in several locations across North America, Europe, and Africa. The answers reflect expert opinions based on available evidence and guidance at the time of publication, and substantial review by experts. Further revisions and additional questions are expected to be added to the information series over time as lessons are learned and evidence improves. In all cases, decision-makers should refer to local laws and guidance where available.

Disclaimer: This first edition of Considerations of risk management of extreme heat during the COVID-19 Pandemic has been produced by the Global Heat Health Information Network. It has been developed in close collaboration with the World Health Organization, World Meteorological Organization, and other government and UN agencies who participate in the expert network. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors, and not the agencies they represent. These considerations are based on available evidence and published guidance at the time of publication (May 25, 2020). It took into account substantive expert reviews. It is the intent of the authors to review and update this content within six months of publication to reflect any lessons and advanced knowledge. Any misinterpretations or inaccuracies are borne by the authors.

-

The following experts in extreme heat and public health participate in the Global Heat Health Information Network. In response to the COVID-19 global pandemic, they have come together to prepare the current considerations and evidence series.

Joy Shumake-Guillemot (Dr.PH), coordinating author, is the lead of the World Health Organization-World Meteorological Organization Joint Office for Climate and Health and co-chair of the Global Heat Health Information Network in Geneva, Switzerland.

Sulfikar Amir (PhD) is Associate Professor of Science, Technology, and Society Sociology Programme School of Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Nausheen Anwar (Prof) is Director of the Karachi Urban Lab, in the Department of Social Sciences & Liberal Arts (SSLA), Institute of Business Administration, Karachi, Pakistan.

Julie Arrighi (MA) is the Urban Manager & ICRC Partnership Lead at Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre and Climate Advisor to the American Red Cross' international programs.

Stephan Bose-O'Reilly (M.D., MPH) leads the "Global Environmental Health" unit at the Institute of Occupational, Social and Environmental Medicine, Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich. As a paediatrician his focus is children's environmental health. As an assistant professor for public and environmental health his focus is on mercury and lead in artisanal mining; and climate change and health care - adaptation strategies.

Matt Brearley (PhD) is a thermal physiologist at the National Critical Care and Trauma Response Centre (Australia) and Managing Director of the heat stress consultancy, Thermal Hyperformance Pty Ltd. Australia

Jamie Cross (PhD) is Senior Lecturer in Social Anthropology at the School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

Hein Daanen (PhD) is a Professor in (environmental) exercise physiology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Francesca de'Donato (PhD) is an Epidemiologist at the Department of Epidemiology Lazio Regional Health Service - ASL ROMA 1, Rome, Italy

Bernd Eggen (PhD) worked at both the Met Office and Public Health England on climate change & human health effects & adaptation of the health system; with expertise on temperature effects on health across timescales and Copernicus Climate Change Services.

Andreas Flouris (PhD) is an Associate Professor at the University of Thessaly Department of Exercise Science in Greece and an Adjunct Professor in Environmental Medicine with the School of Human Kinetics at the University of Ottawa, Canada

Nicola Gerrett (PhD) is a post-doctoral researcher in environmental and exercise physiology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Werner Hagens (PhD) is an environmental health advisor at the Dutch National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) and is responsible for the Dutch Heatwave plan.

Dr. Alina Herrmann (Dr.Med), Institut für Global Health, AG Klimawandel, Ernährung und Gesundheit, Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg, Germany

Maud Huynen (PhD) is a researcher at the Maastricht Sustainability Institute (MSI). Her research interests include sustainability, climate change and health. She is the lead author of the 2019 Dutch Knowledge Agenda for Climate and Health (developed for ZonMw -The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development).

Hunter Jones (MES) (PhD candidate) is the Climate and Health Project Manager for the NOAA, Climate Programme Office, managing projects including the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS), the Global Heat Health Information Network (GHHIN) and other initiatives focused on extreme heat, vector-borne diseases, and other environmental health topics.

Ladd Keith (PhD) is an Assistant Professor in Planning and Chair of Sustainable Built Environments at The University of Arizona, United States. He is an interdisciplinary researcher working at the intersection between urban planning and climate change and explores how climate action planning can make more sustainable and resilient cities.

Aalok Khandekar (PhD) is Assistant Professor of Anthropology/ Sociology, in the Department of Liberal Arts, Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad, India.

Jason Lee (PhD, FACSM) is the Chair of the Thermal Factors Scientific Committee, International Commission on Occupational Health and an Associate Professor in the School of Medicine at the National University of Singapore.

Rachel Lowe (PhD) is an associate professor at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom, with expertise in space-time modeling of the impact of global environmental change on infectious disease risk.

Franziska Matthies-Wiesler (PhD) is Senior scientist at the Institute for Epidemiology, Helmholtz Centre Munich, Germany and previously worked at the Centre for Environment and Health at the WHO Regional Office for Europe, where she worked on preparedness for and response to extreme weather events and was particularly involved in developing guidance for heat health action plans.

Marie Morelle (Prof) is a Senior Lecturer in Geography, University Paris 1 Pantheon Sorbonne, Paris, France.

Nathan Morris (PhD) is a post-doctoral researcher in environmental physiology at University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Claudia Di Napoli (PhD) is a research fellow in Climate and Health specialized in Heat Forecasting and Climatology at the University of Reading, UK.

Anindrya Nastiti (PhD) is Assistant Professor, in the Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia.

Ian Norton (MD) is an Emergency Physician, currently Managing director of Respond Global Health emergencies consultancy, previously lead of the Emergency Medical Team Initiative at WHO creating standards for field hospitals and disaster and outbreak medical response teams.

Lars Nybo (PhD) is Professor in environmental exercise physiology at University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Elspeth Oppermann (PhD) is a researcher on social practices and adaptation in extreme environments, at the Department of Geography, Ludwig Maximilians University, Germany, and a member of the ICOH Scientific Committee on Thermal Factors.

Roop Singh (MA) is a Climate Risk Advisor with the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre focusing on translating science for applications in humanitarian contexts.

Lesliam Quirós-Alcalá (PhD), is an exposure scientist and environmental epidemiologist who focuses on assessing and characterizing environmental exposures in vulnerable populations. She is an assistant professor in Environmental Health and Engineering at the Bloomberg School and an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Maryland Maryland Institute of Applied Environmental Health, United States.

Anouk Roeling (MSc) is a Resilience Officer for the City of The Hague, The Netherlands, focusing on strengthening communities in their efforts to become more (climate) resilient.

Ana M. Rule (PhD) is an exposure scientist with expertise in assessing airborne exposures to environmental hazards. She is assistant professor and director of the Exposure Assessment Lab in the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, United States.

Gerardo Sanchez Martinez (PhD) is Senior Advisor to the UNEP - Technical University of Denmark (DTU) in Copenhagen Denmark. His work focuses on the assessment of social, health and economic impacts of climate change, and tracking the implementation and effectiveness of adaptation policy and activities.

Joris van Loenhout (PhD) is a senior researcher in the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, UCLouvain, Belgium. His research focuses on the health impacts of natural disasters, and in particular heatwaves.

Peter Van den Hazel (MD, PhD) is an environmental health physician in the Netherlands advising on Europe and International policy and programming, particularly related to children's environmental health.

Kirsten Vanderplanken (PhD) is a senior researcher in the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, UCLouvain, Belgium. She studies preparedness policies and health impacts of natural disasters, in particular heatwaves.

Benjamin Zaitchik (PhD) is an associate professor in the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, United States. His research addresses hydroclimatic variability across a range of spatial and temporal scales.

-

These considerations were reviewed by the following experts:

Jonathan Abrahams, World Health Organization, Switzerland

John Balbus, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, United States

Hamed Bakir, World Health Organization, Amman Jordan

Greg Carmichael, Global Atmosphere Watch, University of Iowa, United States

Amy Davison, City of Cape Town, South Africa

Shawn Donaldson, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Kristie Ebi, University of Washington, Seattle United States

Sally Edwards, Pan American Health Organization, Panama

Julia Golkhe, Virginia Tech University, United States

Brenda Jacklitch, NIOSH, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States

Ollie Jay, University of Sydney, Australia

Eddie Jjemba, Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre, Nairobi Kenya

Qudsia Huda, World Health Organization, Switzerland

Aynur Kadihasanoglu, International Federation of Red Cross Red Crescent, Switzerland

Vladimir Kendrovski, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Germany

Pat Kinney, Boston University, United States

Kim Knowlton, Natural Resources Defense Council, United States

Vijay Limaye, Natural Resources Defense Council, United States

Michaela Lindahl, Independent Consultant in Nursing Practice, Baltimore MD, United States

Andreas Matzarakis, Human Biometeorology Research Centre, German Meteorological Service, Germany

Stephen Martin, NIOSH, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States

Emer OConnell, Public Health England, United Kingdom

Jose Reis, City of London, United Kingdom

Sirkka Rissanen, Finish Institute of Occupational Health, Finland

Jrn Rittweger, Professor of Space Physiology University of Cologne, Germany

Paul Schramm, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States

Ross Thompson, Public Health England, United Kingdom

Vidhya Venugopal, Sri Ramachandra University, India

Regina Vetter, C40 Cool Cities Network, United Kingdom

Jon Williams, NIOSH, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States

Appreciation to Sarah Tempest, UK, independent editor for copy-editing services, and Maddie West, WHO Consultant, for production design and editing.